Switzerland mulls controversial Covid-19 health passports

Swiss technology firms and medical researchers are developing digital health passports that could be used to certify who is immune to Covid-19. But scientists don’t yet know whether having the virus confers immunity, and treating people differently based on their immunity status raises serious ethical questions for Switzerland and other countries mulling this option.

Assuming there is such a thing as immunity from Covid-19, the pros of an immunity passport are easy to imagine. The document could be presented to access elder care homes, travel safely internationally, and attend large sporting or cultural events without putting oneself or others at risk. It could be used within medical teams so those lacking immunity don’t come into unnecessary contact with Covid-19 patients. And it could come in handy in strategic sectors to, for example, prevent all the workers at a nuclear power plant from getting sick at once.

The creation of immunity passports is well underway in Switzerland, a country known for valuing privacy and developing quality security products. It is also home to numerous companies working with blockchain technologies, which can provide a secure ledger for the creation and transfer of information.

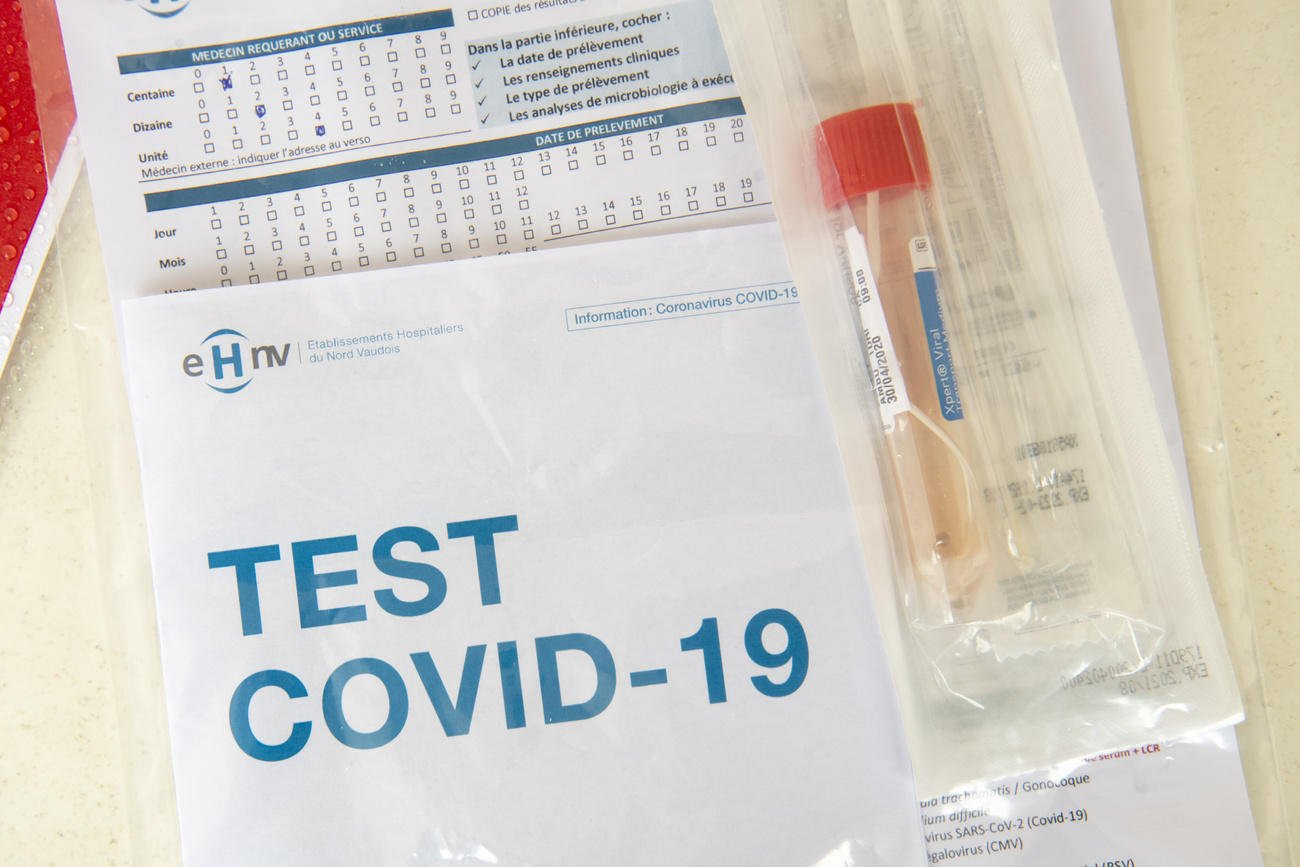

The Covid-19 health passport proposed by SICPA, a Swiss company best known for its work on security inks for currencies and sensitive documents, combines blockchain technology with a QR code. It was developed in partnership with Guardtime, an Estonian company that recently moved its headquarters to Lausanne, to help governments manage the easing of coronavirus lockdowns.

“What our solution proposes is an attestation of the result of a test,” says Philippe Gillet, chief science officer at SICPA. “We associate the issuance of the test and the test result with the person in a very private way. We are securing the data. We are not providing any assurance as to whether the test is efficient or not.”

Another Swiss firm turning to blockchain solutions to provide governments and companies with digital health certificates is Health n Go. The company has used blockchain to distribute tickets for major sporting events in the past and proposes a QR code — acting as a sort of certificate — that can be presented on a smartphone’s wallet.

“Certificates can be revoked remotely; they can have expiry dates; or they can be centrally managed whilst preserving the data privacy of the holder,” says Frédéric Longatte, CEO of Health n Go. For example, he explains that an immunity certificate could be revoked if a batch of test kits were found to be unreliable, making the test result invalid.

Ethical considerations

But some feel it’s too soon to develop immunity passports without a full understanding of how the virus works and the ethical implications.

“The real significant risk here — setting the question aside for a second about whether and to what extent immunity exists — is that you are creating this perverse incentive for people to go out and catch the virus and develop an immunity, and this is a very dangerous, deadly virus,” says Brent Mittelstadt, a data ethics specialist at the Oxford Internet Institute.

He finds linking immunity to the right to work or the possibility of having normal access to services, shops and restaurants to be an extremely harmful stratification of society. He is also concerned about passport holders’ privacy.

“Immunity passports are being discussed as a way to basically give you back fundamental rights that have been restricted or taken away under a state of lockdown,” he says. “My main concern is using Covid-19 as a lever to get more invasive technologies through the door.”

“It’s a question of what is the baseline,” says James Davis, professor of international politics at the University of St. GallenExternal link. He sees them as a step in the right direction when the only alternative is to stay shut down for a long time until a vaccine or treatment is developed. “I understand the concern that it would give people who have immunity an advantage, but it also provides an advantage to society as a whole because we’re opening up the economy faster,” he reckons.

Moving ahead

Despite such concerns, the idea of linking freedom of movement to coronavirus test results appears to be gaining ground as testing becomes more widespread and countries rush to restart their economies and ease lockdowns. Chile was the first country to provide certificates to people who have recovered from Covid-19, although the Latin American nation had to backpedal and rebrand its immunity certificates as “release certificates” after weeks of global debate on whether recovered patients are actually resistant to the virus.

The pros and cons of immunity passports are being mulled in the UK and US, as well as hotly debated across Europe. German ethics experts are looking into it at the government’s request. “The question of what it means for society when some people are hit by restrictions and others are not, that touches on the foundations of how society functions together,” German Health Minister Jens SpahnExternal link said earlier this month after securing millions of new coronavirus tests from Swiss drugmaker Roche.

The World Health OrganizationExternal link cautions that such certificates could increase rather than reduce the risk of continued transmission. Some people may assume that they are immune to a second infection because they have received a positive test result and therefore ignore public health advice.

“At this point in the pandemic, there is not enough evidence about the effectiveness of antibody-mediated immunity to guarantee the accuracy of an ‘immunity passport’ or ‘risk-free certificate’,” the Geneva-based body wrote in a scientific brief.

But that assessment — like so many others made in relation to Covid-19 — could well change with new evidence.

Scientists want to be prepared

In Switzerland, efforts are cautiously underway to assess immunity and how best to handle immunity information of recovered Covid-19 patients. The Swiss National Covid-19 Task ForceExternal link has issued a paper tackling the ethical aspects of serological tests which detect antibodies produced in response to the virus. And the Swiss School of Public HealthExternal link is developing a nationwide study on the seroprevalence of antibodies against the new coronavirus.

“Before the science shows us that these people have more protection, we have to be very careful,” says Idris Guessous, head of the primary care medicine team at the Geneva University Hospitals. “It’s a matter of time before we know.”

Guessous and his colleagues are currently running large serological studies to check for Covid-19 antibodies at his lab and carrying out a random study with 6,000 people to help measure how widely the virus has spread in the Geneva area. The two main hurdles he sees to introducing immunity passports are the low percentage of the population that has contracted the virus (estimated to be less than 10% in Switzerland) and uncertainty over whether having antibodies against Covid-19 means a reduced risk of contracting the virus again. Political and ethical hurdles must also be overcome before digital immunity certificates are introduced.

The Geneva-based researcher firmly believes in exploring immunity passport solutions so that they are ready to go if needed. That could be the case if Switzerland faces a serious second wave of infections, and it’s part of why he has teamed up with SICPA to try out their blockchain certification solution. As a starting point, says Guessous, the technology could be used to certify the presence or absence of antibodies, then evolve into an immunity certificate if there is proof that antibodies reduce the risk of infection. In the absence of a vaccine, the app could nudge people to get tested for antibodies again to ensure they remain immune.

His academic study on immunity certificates in Geneva, which will be submitted for review by an ethical committee in a few days, will also integrate a survey to help assess the general population’s openness to the idea.

“We are working on the what-if scenario,” he says. “We are doing this just in case we as a nation decide to use it. WheTther it’s for the military only, whether it’s for healthcare providers only, pilots only, who knows.”

But Switzerland’s Federal Office for Public Health says the introduction of Covid-19 immunity passports is not on the agenda for now.

“It’s far too early,” spokesman Grégoire Gogniat told swissinfo.ch. “Provided that we have confirmation that the antibodies do indeed lead to long-term immunity, it could make sense. It will also become relevant as soon as a vaccine is developed.”

More

Coronavirus: the situation in Switzerland

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.